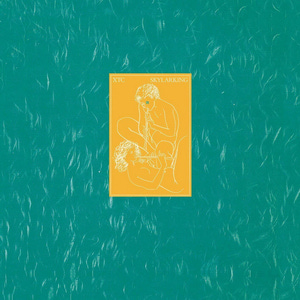

It's hard nowadays to imagine XTC’s Skylarking without the crown jewel of “Dear God.” But the song was famously not even supposed to be on the album. It created controversy amongst the band, the producer, and the record label.

For starters, songwriter Andy Partridge felt his song about God (or the lack thereof) was maybe too big of a subject to tackle in a pop song. In a 2006 interview with Todd Bernhardt, Partridge said “It wasn't on the original album because I honestly thought that I'd failed. It's such a vast subject -- human belief, the need for humans to believe the stuff they do, and the many strata involved, the many layers of religion and belief and whatnot. So, I thought I'd failed to address this massive subject for all mankind -- and also a big subject for me, because I think it'd been bugging me for many years. I'd struggled with the concept of God and Man and so on since I was a kid, even to the point where I got myself so worked up with worry about religion that -- around about the age of 7 or 8 on a summer's day -- I saw the clouds part and, you know, there was this sort of classic Renaissance picture of God surrounded by his angels looking at me scornfully.”

In the conservative 1980s, and even coming out of the wilder decades of the 60s and 70s, there were only a handful of songs that dared to grapple with such a weighty topic. There was John Lennon tackling the subject in his songs “God” and perhaps even “Imagine” (“imagine there’s no heaven, it’s easy if you try…”). “Jesus Christ Superstar,” though appearing to be friendly towards Christianity, definitely had a deeper critique of the religion lying under its technicolor dream coat. And then there’s “Blasphemous Rumours,” the 1984 song from one of XTC’s contemporaries, Depeche Mode. It might not have been as upfront about its questioning as “Dear God,” but the intent seemed just as obvious: “I think that God's got a sick sense of humor / And when I die, I expect to find Him laughing.”

At the time, perhaps the idea of tackling such a topic in a 3-minute pop song was too much to ask and therefore the canon of songs that were critical of religious beliefs or downright atheist in nature were fairly uncommon. In the decades after the release of “Dear God,” there seemed to be a whole slew of artists questioning their belief systems: Tori Amos’ “God,” Nine Inch Nails’ “Terrible Lie,” the Sugarcubes’ “Deus.” Even hair metal band Poison got into the game with their 1990 song, “Something to Believe In.” And in 1992, Sinead O’Connor famously tore in half a picture of Pope John Paul II. But in 1986, there was a rather shallow pool of songs addressing the topic.

Colin Moulding remembers being taken aback that the song was pulled from the initial running order, telling me in 2022, ““It was actually taken off the record at Andy’s request. I thought it was a bit odd… It was in Todd’s original order. I don’t know if it had something to do with Andy feeling disgruntled with Todd’s production or method of recording but he got a bee in his bonnet and said he didn’t want it on the record. He said he hadn’t written it in the pointed manner that he’d hoped he would do or something. In any case, he wanted it off the record and he wanted another track put on which the record company got behind him to do and that was “Another Satellite,” which if you listen to it is slightly at odds with the rest of the material I think.”

Producer Todd Rundgren put it to podcaster Marc Maron a little more bluntly: “We delivered it and a couple of weeks later I get, ‘Ok we’re going to change the running order of the record. We’re taking Dear God off the record’. We’re gonna take the hit record off the record?! He was afraid that there would be repercussions personally for him for taking on such a thorny subject. What a pussy.”

******

A key element of the song that many can’t imagine not being there is the child singing a verse at the start of the song.

Jasmine Veillette was around nine years old when she was recruited to sing the opening lines of the song by a friend of her family and employee of Todd Rundgren’s, Ralph Legnini. Veillete’s father was a well-known maker of guitars in the area and was known to sing and perform. The band was a bit of a family affair and Veillette started singing with them when she was just five.

“It started with the theme song for ‘Scooby Doo.’ They worked up a doo-wop, acapella version of it. So, they would drag me up and I would sing on that. I would do pretty much one song every gig that they did.”

Legnini would come to these gigs to watch his friends play and occasionally sit in with the band.

“All of a sudden, they need a kid to sing. They needed a kid that sounded like a kid but was professional enough to not really need to be schooled. They didn’t want it to be professional like a Broadway singer kid. They wanted it to be really natural. They didn’t want to really work a lot with the kid either. He [Todd Rundgren] happened to ask Ralph if he knew of any local kids that can sing and he had just seen me sing with my parents like a week or two before that so I was fresh in his brain.”

She didn’t know anything about the band and was told they were from England. She remembers saying something like, “Oh, that’s where the Beatles were from.” Rundgren gave Legnini a cassette with a rough demo of the song and what they were looking for. Veillette’s father told her to put it in her tape recorder and asked her to listen to it and learn and see if it was something she wanted to do. The song on the cassette was just the first verse and would fade out with Andy Partridge’s vocals came in.

She only had a week or so to learn the song before her father drove her to Todd’s studio, Utopia, where it was just herself, Todd, an engineer, and Legnini. Rundgren told the band to leave the studio so as to not make her nervous, but Jasmine later heard that they didn’t go too far and actually peeked in the windows to watch what was happening. They practiced once or twice than ran the tape – the whole experience lasted about an hour.

Later, after the song came out, she sang on Charlie Sexton’s cover of Gerry McMahon’s “Cry Little Sister” off the Lost Boys soundtrack. He specifically requested “the girl who sang on ‘Dear God.’”

Veillette says now “I think it’s pretty amazing how it’s still relevant, almost more so now than it was then. I don’t know what the catalyst for the song was but it certainly resonated with a ton of people.”

It was this major element to the song that presented another theory as to why the song was left off the final track listing.

“Both Andy and I hated the kid’s vocal on the first verse. We hated kids singing on pop records FULL STOP! Loved the song, but hated what Todd had specifically done in that regard,” said Jeremy Lascelles, XTC’s principal A&R person at the time

It was Lascelles’ job to help them make the best possible record they could. That could involve suggestions and discussions about possible producers, song selections, album sequencing, choice of singles, and things of that nature. He started working with the band in 1980, with their Black Sea album, and continued through Skylarking and Oranges & Lemons.

He continued, “So, it was our absolutely mutual decision to remove the track - I think we substituted it for “Another Satellite.” No pressure from the record company about it being too controversial or that it might cause offense, or any other nonsense that I have read in various books and articles subsequently. Purely a musical decision. We were wrong, weren't we!”

******

When Skylarking was first released in 1986, the running order did not contain “Dear God” but “Another Satellite” was there in its place. The first single released was “Grass” and they relegated “Dear God” to the B-side.

Songs that were placed on the B-side generally seemed like cast-offs, experiments, or sonic gifts for the collector who wanted a comprehensive collection of the work from their favorite artist.

Michael Zilka, who ran ZE Records from 1978 to 1984 and helped build the careers of Was (Not Was), The Waitresses, and Cristina, says, “There wasn’t a lot of thought into the B-side. I never wanted to put out anything I didn’t love though so it’s not like the B-side didn’t matter to me. The B-side was possibly less commercial. Sometimes, I would consider the song on the B-side to be more radical. Was (Not Was) first single ‘Wheel me Out’ had ‘Hello Operator’, a much more aggressive song. That was a side of them I never wanted to abandon.”

Oddly enough, Zilkha had his own experience where the B-side to one of his records went on to overshadow the intended single. “The first big hit we had, ‘Deputy of Love’ by Don Armando’s 2nd Avenue Rhumba Band which was a number one dance record was actually the B-side. ‘I’m An Indian Too’ was the A-side. And we had it completely wrong. Thunder Ray, who was the singer on that, kept telling us we had it wrong and we released it anyway. Sure enough, the B-side took off.”

* * * *

But a funny thing happened on the way to ‘Dear God’ vanishing into obscurity. Radio DJs flipped the record to see what was on the other side.

Radio stations at the time were not as rigid as they seem nowadays. They definitely had a playlist and songs they needed to play, but there was a certain amount of flexibility. Radio station DJ Rick Stuart, a DJ at The Quake in California in the mid-80s, says “They were open to the fact that the DJs liked the music, the DJs knew the music, and the DJs could creatively program the music.” That said, it was not common practice to flip a record over to play what was on the other side. Things like that were often relegated to late night shows or Sunday evenings. Other than that, Stuart says “you didn’t come in with your box of records and decide to just start playing B-sides.”

It was DJ Roland West from Los Angeles’ influential radio station KROQ who was one of the first American DJs to play the record. For any artist to get played on KROQ was a big deal.

West told me, “Back then, the DJ's were given a 'choice' selection once an hour to play something 'off the playlist', a personal discovery, whatever they had in mind. I was fortunate to have an amazing intern, Randy Divine, who tipped me to many great imports and new singles, including the XTC B-side ‘Dear God.’ I was a huge XTC fan from years ago while a college DJ, so playing them was a no-brainer. The song, lyrically/musically, was like nothing else we were playing at the time. It hit me hard the very first time I played it and reacted quickly with listeners as well. It wasn't too long before 'Dear God' was being played regularly on KROQ and a select few other modern rock stations. The reaction was mixed to be sure, mostly positive, but it definitely got people talking and listening… the program director Rick Carroll was always keen to recognize a song that stood out and garnered attention. It’s what KROQ was all about and this song did just that.”

Moulding, who wrote “Grass,” was not necessarily disappointed that DJs chose Partridge’s song over his. He laughed and said, “I think I was just grateful to have a hit!”

And it did become a hit! For some artists, courting controversy is their way to move units and fill arenas: the stage theatrics of Alice Cooper and Ozzy Osbourne, risqué videos and every other single released from Madonna, the shock-your-parents vibe of Marilyn Manson. Controversy has been good to these artists and a way to build their career. This was never XTC’s way – sure they had some interesting costumes that grabbed attention but they were more likely to be dressed as pilgrims or deep-sea divers rather than posing in their underwear or releasing explicit songs about sex or devil worship.

“Dear God” wasn’t planned; it was accidental in every sense of the word. It was held back for fear of generating controversy and it was never really planned to be a radio hit, let alone the hit that would turn the band’s fortunes around. It reached college-age ears on their terms and I’d like to think it’s the song’s beautifully strummed melody that struck a chord and not necessarily the message of the song.

Moulding says of its popularity amongst the college crowds, “I think college kids are a bit more daring, aren’t they? They liked it because it was controversial. It wasn’t a Top 40 hit with mainstream America. It was a hit amongst college kids who liked controversy more.”

As the song escalated in popularity, American mainstream listeners indeed were not pleased. Partridge received letters and death threats, there was a bomb scare at a radio station in Florida, the infamous incident at the school in Binghampton.

Partridge told BBC4 Radio’s podcast The Voices of…., “I wrote a song called ‘Dear God’ and I got some really threatening letters from supposed Christians. The nicest things they were telling me was that I was going to burn in hell. That was the nicest thing”

“Some people harkened back to the John Lennon quip I think,” Moulding told me, referencing Lennon’s “the Beatles are bigger than Jesus” moment. “Oh no we’re going to upset somebody, you know. Our record is going to be burned in the street. But, it was just an opinion, that’s all….. I can’t say we had the furor we had in the States anywhere else.”